Emily Bell, the former Guardian digital editor who now runs the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, gave a speech recently at the Reuters Institute in the UK about the crossroads at which journalism finds itself today. It’s a place where media and journalism — and in fact speech of all kinds — has never been more free, but also paradoxically one in which speech is increasingly controlled by privately-run platforms like Twitter and Facebook.

I was glad to see Emily addressing this issue, because it’s something I’ve written about a number of times — both in the context of Twitter’s commitment to being the “free speech wing of the free-speech party,” and also in the context of Facebook’s dominance of the news and how its algorithm can distort that news in ways we still don’t really appreciate or understand, because it is a black box.

Get all the news you need about Media with the Gigaom newsletter

“Today… we have reached a point of transition where news spaces are no longer owned by newsmakers. The press is no longer in charge of the free press and has lost control of the main conduits through which stories reach audiences. The public sphere is now operated by a small number of private companies, based in Silicon Valley.”

Free speech vs. profit

As Emily pointed out, it’s a serious issue not just for journalists or the media but for society as a whole to have “our free speech standards, our reporting tools and publishing rules set by unaccountable software companies.” Although these platforms often say they are in favor of free speech and other principles, as Twitter does, at the end of the day they are profit-oriented public companies who must pursue certain ends in order to generate revenue.

There’s also a certain tendency on the part of these platforms and their executives to deny that they act in any kind of editorial role or perform any kind of journalistic function, when they clearly do. In an interview with the New York Times, the Facebook executive in charge of the main news feed said he doesn’t think of himself as an editor — and yet, algorithms involve editorial choices of what to include and what to leave out, even if Facebook and other companies don’t want to admit it.

“No other single branded platform in the history of journalism has had the concentration of power and attention that Facebook enjoys… If one believes the numbers attached to Facebook, then the world’s most powerful news executive is Greg Marra, the product manager for the Facebook News Feed. He is 26.”

This power is often exercised in disturbing ways: Facebook repeatedly removes content that doesn’t meet its standards, but often doesn’t say why — and in some cases this can affect the historical record of important events, such as the Syrian government’s use of chemical weapons against its own people, as the investigative blogger Brown Moses has described a number of times.

Then there’s the algorithmic exclusion of certain content, as sociologist Zeynep Tufekci described in the aftermath of the civilian unrest in Ferguson, Missouri following the police shooting an unarmed black man. That kind of filtering has serious social implications, Tufekci pointed out, just as much or more than issues like net neutrality.

Media vs. technology

It’s not just Facebook, either — Twitter has also removed content, such as the beheading videos circulated by the militant Islamic group ISIL, and has also blocked accounts and in some cases banned them completely after being forced to do so by governments of various countries or the courts in those countries. These are editorial decisions that affect our view of the world.

“In 2010 Facebook conducted another experiment to see whether issuing voting prompts in certain feeds increased turnout. It did in fact. As Harvard Law Professor Jonathan Zittrain asked: What would happen if the Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg decided to tweak an algorithm so that only voters who favored a particular party or candidate were prompted to vote?”

So what can we do about this? Emily’s suggested solution — or at least part of it — is for media entities of various kinds to spend more time trying to “build tools and services which put software in the service of journalism rather than the other way round,” instead of just using the platforms designed by non-media companies. “We need a platform for journalism built with the values and requirements of a free press baked into it,” she said.

Having been around for at least as long as Emily has, I am skeptical — as I think Jeff Jarvis also is — of the media industry’s ability to come up with a technological solution on their own. Many existing media entities, even the large ones, have trouble putting together a functioning webpage or mobile app, let alone building an entirely new kind of social communications platform.

But we should keep in mind that it is technology that broke the hold of media moguls & corporations over journalism. http://t.co/CBLyBEOUNg

— Jeff Jarvis (@jeffjarvis) November 22, 2014

The genie has escaped

I also agree with Jeff that the technological revolution or disruption that Emily describes has had one massive benefit in journalistic terms: namely, it “broke the hold of media moguls and corporations over journalism,” as he put it on Twitter. That’s something we shouldn’t ignore in our desire as journalists to recapture the control over the tools of media that we used to enjoy.

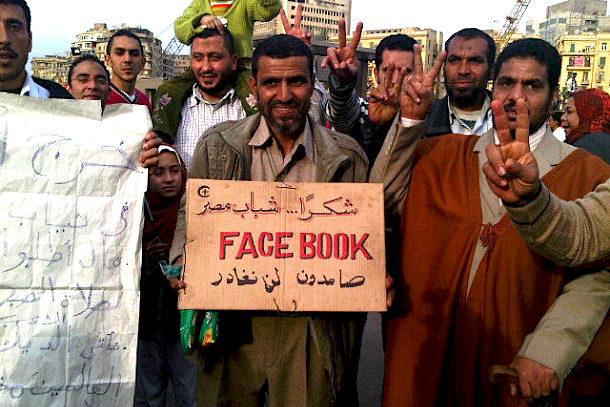

On that note, I was glad to see that Emily mentioned in her speech that professional journalism is now “augmented by untold numbers of citizen journalists who now break news, add context and report through social platforms.” That is an incredibly powerful (and also inherently chaotic) feature of the web, and it has broadened the pursuit of journalism immeasurably — more that many traditional journalists would probably like.

Where I agree with Emily is that it is problematic that all of this expanded journalistic activity (both professional and amateur) and speech of all kinds occurs primarily through proprietary platforms that may not feel any commitment to the principles that media insiders believe should apply to that behavior. What can we do? We can try to apply pressure, as Jarvis argues in a post.

In the end, however, journalism will take whatever shape the journalism-consuming public wants it to take. We can try to influence that, but for better or worse the genie is pretty much out of the bottle and operating on its own now. How we handle that is up to us to decide.