Ten years ago, California State Senator Liz Figueroa raised concerns over a definitely-not-evil company called Google that had been tracking keywords through its Gmail service, servicing ads to Gmail users and non-users alike based on that data. Her worry was less over the marketing tactics, and more over the possibility that Google would keep a digital dossier of all its users. Google claimed it would not do this, so Figueroa saw no harm in proposing a law to help keep the company to its word. That bill never passed the California House.

Now, ten years later, we know that Google did go on to keep user data indefinitely, and even offer it up to governments by request. And the user data retained by tech companies is no longer limited to keywords in emails. Smart thermostats like Nest (owned by Google, naturally) collect our heating and air conditioning data. Trackers on cars collect our driving data. All manner of smartphone apps capture our location. And perhaps most disturbingly, smartwatches and other fitness trackers collect our health data.

In some ways, we find ourselves in the same position we did 10 years ago, albeit on a much larger, more physical scale. There is vocal opposition to new forms of data tracking, but little in the way of real legislative reform to govern it. If lawmakers once again fail to keep up with the big data collection practices of tech companies, can you imagine where we’ll be ten years from now?

This is the narrative that frames a new graphic novella from Al Jazeera America titled “Terms of Service: Understanding Our Role in the World of Big Data.” Written by Al Jazeera reporter Michael Keller and cartoonist Josh Neufeld, who also drew the artwork, the novella explains the history of big data and the ramifications its collection has on user privacy in a format that’s smart, breezy, and beautiful.

Skeptical? I was too, at first. Having experimented with plenty of formats for journalistic storytelling myself, I know it can go well — but I also know it can fail miserably. Substance can be sacrificed to style. In extreme cases, like Mike Daisey’s dramatic monologue on Apple’s factory workers in China, the truth gives way to the lure of a great narrative.

But make no mistake: “Terms of Service” is a rigorously reported piece of journalism — there are numerous “characters,” from Figueroa to University of Colorado Law professor Scott Peppet, and everything they say is a direct quote, either transcribed by the reporters or taken from a transcript.

Along with the expert interviews, the bulk of the narrative takes the form of a conversation between Keller and Neufeld.

“We were trying to evoke a feeling of Radiolab or a(nother) NPR show,” Neufeld said. “A feeling of two people who are your close friends, talking about a subject, kicking down different paths.”

Before partnering up, Keller was familiar with Neufeld’s work, most notably his acclaimed 2009 graphic novel of Katrina, “A.D.: New Orleans After the Deluge.” But they were not yet close friends. And yet as they learned more and more about each other, their casual conversations over things like Foursquare check-ins and self-driving cars greatly informed the narrative.

“We included a lot of spontaneous conversations we had that might not have happened had we known each other well,” Keller said.

But why a comic? Why not a radio show, if those were the rhythms Keller and Neufeld sought to capture? After all, journalism budgets aren’t exactly begging for months-long projects that require top-tier artistic talent from outside the organization.

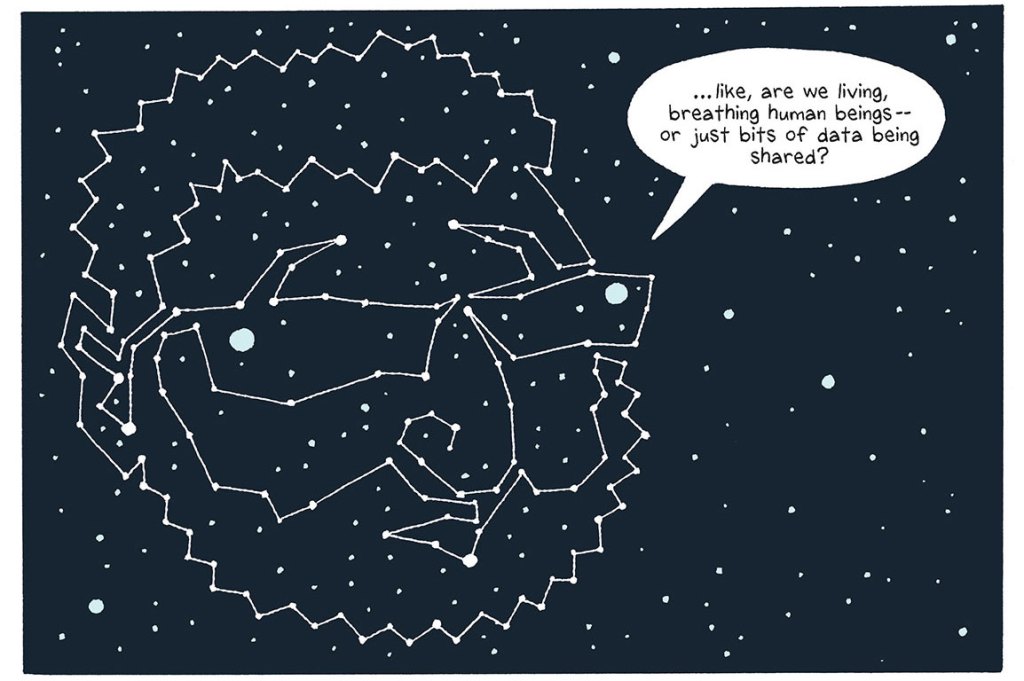

Neufeld says that “comics journalism” allows for the representation of abstract concepts in ways that written or spoken-word pieces simply can’t. For example, at one point the protagonists describe how all these different data points about a person — the food they buy, the amount of exercise they get, how often they drive — can be connected by marketers, governments, or insurance companies any way they like. By connecting these dots, like stars in a constellation, they can draw a picture of you that, while technically accurate, is really an ugly distortion of the real human being behind the data. That’s not something easily communicated by words alone.

One of the hottest journalistic buzzwords of 2014 has been “explainer.” And strictly speaking, “Terms of Service” qualifies, as it lifts the veil off a complex issue using conversational language. But in my mind it’s eons ahead of most of what the two big explainer outlets, Vox and FiveThirtyEight, have put out to date. That’s because it doesn’t simplify the issue of big data and user privacy so much as it captures its complexity, through a combination of storytelling, reporting, and visual abstraction. And most importantly, the story isn’t closely pegged to the latest big data developments or breaking news. Instead, it’s told in a way that allows for sustained relevance — the mark of a truly great explainer.

“This is a piece that is not just about the latest gadget or the latest spyware,” Neufeld says. “It’s about concepts and issues that are gonna be something we’re confronting and dealing with for quite a while.”